WHO ARE DOMESTIC WORKERS?

“It is my dream that I will see domestic workers respected like other workers. It’s my dream that exploitation, low salaries and other forms of violence will not take place.”

Angel Benedicto, former domestic worker and current activist

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines “domestic work” as work performed in or for one or more households. “Domestic workers” are defined as all people engaged in domestic work within an employment relationship. This definition allows us to capture the great variety within this group: a domestic worker may work full-time or part-time, live in the house of the employer (live-in) or have her or his own place of residence (live-out). Domestic workers can be hired directly or via private employment or recruitment agencies. It is not unfrequent even to carry out this kind of work within one’s own family. Domestic workers may do a number of different tasks, from cleaning, cooking and washing to gardening or driving for the family. Many work with people who need care, such as children, persons who are elderly, sick, or with a disability. In different countries domestic workers are called in different ways, such as maids, servants or helpers, but these derogatory and condescending terms fail to acknowledge their efforts as real workers.

According to the ILO, currently there are at least 67.1 milions adult domestic workers worldwide, but this number is likely to be much higher due to high informality and irregularity in the sector, as well as lack of reliable statistics based on univocal definitions and criteria. Most domestic workers concentrate in Asia and Latin America, but the situation is different when we consider only those of migrant background as half of them work in North America and Europe.

Today the demand for paid domestic and care work is rapidly growing. Three main trends, with varying regional differences, have been associated with growth in domestic work:

- integration of women in the labour market: increase in women’s employment, passage from single to dual wage-earning families;

- changes in population trends: rapid population aging, increasing life expectancy, and lower fertility rates;

- changes to welfare and economic policies: neo-liberal macro-economic policies tightening social policy budgets, weakening public care services, and delegating them from the government to families. [2]

In particular in the ‘global South’, demand for domestic and care workers has grown exponentially in recent years, and it is expected to continue in this direction. This trend is especially pronounced in the Gulf States and the Levant.

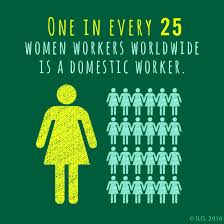

Women disproportionally carry out most of unpaid domestic and care work all over the world. For domestic and care work under employment conditions the situation is not different. Although part of domestic work is carried out by men, especially in roles such as gardeners, family drivers and house guardians, this sector is highly and traditionally feminized. Indeed, more than 80% of domestic workers worldwide are women and girls, making up 1 in every 13 female wage earner.[3]

Unpaid and paid care and domestic work are deeply interrelated: they both stem from gender-based social norms and practices. In other words, household and care tasks are still predominantly seen as a “women’s job” and underpaid, if paid at all. To change the situation, the recognition of the social significance and economic value of care and domestic work should be at the top of the agenda for gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. This can be achieved by dismantling entrenched gender stereotypes and redistributing these responsibilities more evenly between men and women, and between families and the state.[4]

Nearly 1 in every 5 domestic workers is an international migrant. According to ILO estimates, there are 11.5 milions migrant domestic workers and they concentrate mainly in high income countries, in North America and Europe, and come largely from lower income countries within the same region or from Latin America and Asia. Most migrant domestic workers are also women (74%), with the notable exception of the Arab states, which accounts for more than half of all male migrant domestic workers in the world.

Nowadays a global care work chain leads women from contexts lacking decent work opportunities and characterised by increasing inequalities to emigrate to wealthier countries in search of better possibilities. Even though they often do not look for domestic work, high demand and low entry barriers drive them into the sector.

Labour deficits and criminal abuse

Domestic work contributes significantly to the economy and society, sustaining households, fostering productivity, economic growth, and human development. However in order to maximize these contributions enjoyment of rights and fair working conditions by domestic workers is necessary. The experience of each individual domestic worker varies greatly, but too many face serious work deficits, are exposed to high risks of discrimination, and have limited resources to react to injustices. Factors relating to gender, nationality, etnicity, social class and social status all intersect in placing domestic workers in a disadvantaged position.

The main particularity of this job is where it takes place: within the household. Shifting the place of work from a public space to the private sphere limits the possibility to control working conditions, enforce labour laws and limit abuse. Increased inspection is much needed to stop exploitation and harmful dependency in hidden workplaces, as stated by the EU Fundamental Human Rights Agency.[5] Another key aspect is informality. Informal work in general is marked by severe work deficits, particularly among vulnerable groups such as the one treated here. This has led ILO to adopt in 2015 a recommendation on the topic. [6]

Those factors lead to alarming rates of wage exploitation, lack of rest, excessive working hours, inadequate living conditions, lack of access to care, arbitrary terminations of contract. This happens all over the world. In the U.S., most domestic workers are paid less than half of the federal minimum wage. Unpaid wages is the most common complaint from Filipino and Indonesian migrant workers. Across all continents, it is normal for domestic workers to work between 14 and 18 hours per day. Many also suffer long-term health problems as a consequence of this work and/or of violence in the workplace. In Honduras, up to 25% of women in these jobs have reported serious burns, cuts and contusions. From one day to the next domestic workers can find themselves jobless. In the Middle East, there are laws that prescribe job termination in case of pregnancy. Many Indonesians in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia have reported being fired and forced to repatriate after telling their female employers about sexual harassment from male members of the family. Vulnerability to sexual harassment and assault is even higher for live-in workers, often forced to sleep in common areas, without a lock, or in shared rooms.

Psychological, physical and sexual abuse are also common phenomena. Almost all domestic workers are subject to some form of mistreatment, from verbal abuse and threats, to beatings, to rape. The death of an Indonesian domestic worker in Singapore is a striking example: the autopsy revealed that she was beaten to death and that over 200 injuries were done on her body. Those who denounce abuse are often blamed and not believed even by the authorities. In some countries such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait those who find the courage to denounce in turn risk prosecution for adultery or fornication. In El Salvador, this kind of abuse is one of the most common causes among domestic workers for changing employer or job.

There are numerous known cases of domestic workers also being deprived of food, forced to work as slaves, and trafficked. A study found that in Haiti domestic workers weighed on average 20 kilos less then other people living in the same neighborhood. Domestic workers, especially migrants, often find themselves in circumstances that can only be described as forced labour: locked in the employer’s house, stripped of their documents, under threats from employers and agencies. Trafficking happens in high numbers to people ‘recruited’ for domestic work, in particular under-age individuals. The family usually comes from a poor, agricultural background and is falsely promised that the child would receive an education and professional training. On the contrary, the girls end up being exploited and unpaid, in a situation that can be called slavery. [7]

Women who are migrant domestic workers often face even greater challenges compared to their national counterparts. They are more isolated and exploited in light of their language, nationality, lack of social support, and limited knowledge of the local laws and customs. For those who have irregular migration status or whose visa is tied to the employer, it is even more difficult to leave an unhealthy employment relationship. This malpractice is very common in Arab countries, where a kafala or sponsorship system is in place.

Indeed, the situation is particularly critical in the Gulf countries, as denounced by the Human Rights Watch.[8] There, almost all families employ domestic workers, who often are migrants from South Asia and Africa, work between 60 and 100 hours per week and earn less than 30 percent the average wage. Even if only few of those abused find the courage to denounce, embassies, consulates, and centres for domestic workers receive tens of daily visits from women who want to escape exploitation and violence. These terrible experiences and the humiliating and frustrating attempts to put an end to them or to receive redress lead to frightening rates of suicide among migrant domestic workers in these countries. [9]

STEPS TOWARD DECENT WORK FOR DOMESTIC WORKERS

“All work has dignity. We must stop being servants, the lowly ones, those people who deserve nothing. Now, for the first time, we can speak on our own terms.” Juana Flores, National Domestic Workers’ Alliance, USA [10]

In order to tackle the complex situation described above, many advancements need to be made, internationally and locally, on different fronts – namely, the promotion of decent work for domestic workers, gender equality, and policies that look after the rights of labour migrants. In the first area, a cultural and value shift is needed towards the professionalisation, formalisation, and recognition of domestic work. This needs to be coupled with efforts to create a more balanced and equal world from a gender perspective in all areas of life, including the employment sphere, decision making, the family, etc. Concerning migration, it should be first of all assured that it is a choice rather than an obligation, through the creation of decent work opportunities for women, both at the country of origin and the country of destination, and the fight against human trafficking.

International conventions and resolutions

During the 100th session of the International Labour Conference on the 16th of June 2011, the ILO adopted the first international convention targeting domestic workers specifically. Convention No. 189 starts from the fundamental premise that domestic work is historically undervalued and traditionally done by women. Those employed in this sector deserve recognition, respect and rights equal to other workers, yet their unique circumstances and characteristics need to be considered. This Convention is viewed as a crucial step towards ILO’s goal of decent work for all.

Over all, the Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189) sets minimum standards that can be expanded over time. It also puts an emphasis on the importance of consulting with workers’ and employers’ representative organizations for its effective implementation at the local level. Recommendation No. 201 was adopted in order to provide guidelines for the implementation of the Convention.

Convention No. 189 and the associated Recommendation have come into force in September 2013, after the first ratifications by Urugay and the Philipines, two important countries of origin. To date, 23 countries in the world have ratified, of which 12 are Latin American, 7 European, 3 in Africa and only the Philipines in Asia. According to the ILO, 17 national governments have also adopted laws or policies consistent with the Convention’s aims. Governments which ratify this Convention and improve their legislation according to its principles can take significant steps to advance the conditions of domestic workers. [11]

The EU authorised Member States to ratify the Convention in 2014.[12] The first one to do so was Italy, also the first destination country to ratify. In 2016, the European Parliament adopted a Resolution on women domestic workers and carers (2015/2094(INI)), calling for their professionalisation and social protection, and one on creating labour market conditions favourable for work-life balance (2016/2017(INI)) in which they addressed the need to reduce the gender gap in hours of unpaid care and household work. This is also a central objective for the European Commission’s strategy for gender equality 2016-2019.

Other important documents adopted by UN agencies on the subject include the General Comment on migrant domestic workers adopted by the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (CMW), 2010; and the General Recommendation No. 26 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) on women migrant workers, 2008, which also addresses domestic workers. In 2012 UN Women collected these inputs in a guide based on a Checklist to protect and support domestic workers.

The crucial role of civil society and unions [13]

One of the main barriers to effective protection and abuse prevention is the lack of knowledge about rights and the voice to uphold them. To combat this obstacle, there is the need to empower domestic workers and to strengthen the structures and organizations that represent them. However, domestic workers are in many countries denied the right to organise and, where there is no such obstacle, isolation and geographical dispersion of their place of work, long and irregular working hours, limited freedom of movement, a particular employer-employee relationship, all make collective organising difficult. Nevertheless, thanks to the efforts of many vocal and brave domestic workers, nowadays the situation is improving and more organisations of domestic workers exist all over the world.

Domestic workers’ experiences in organising and mobilising often take place within, or are supported by, migrant and informal workers’ organisations. In North America and Europe, activism by and for domestic workers was often propelled by migrant associations and groups. For example, the U.S. National Domestic Workers’ Alliance (NDWA) was born from the efforts of domestic workers of migrant origins in New York. Other important examples in the world include the Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA), the large association of overseas Filipino workers Migrante International, the European NGOs PICUM, RESPECT and SOLIDAR, the global network for Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), as well as anti-trafficking and anti-slavery networks. Unions and workers’ confederations are other essential entities for domestic workers to gain support, voice, and representation, allowing them to effectively employ social dialogue and collective bargaining in negotiations concerning legislations and regulations that affect them, as it happened in Argentina, Belgium, France, Italy, and Uruguay, just to mention some. Unions and other organisations have also contributed significantly to the capacity and skill building of domestic workers, further promoting activism.

Domestic workers have united in organisations at a local and national level for decades but global mobilization came only recently, giving birth to powerful networks like the International Networks of Workers in Domestic Service, which now has become the International Domestic Workers’ Federation (IDWF), founded in 2013 and counting today 59 affiliated organisations in 48 countries. The IDWF is a network of trade unions, associations, and workers’ cooperatives with the aim of protecting and advancing the rights of domestic workers everywhere. They provide a platform and useful resources for individuals, organisations, and policy-makers, creating a global and regional community to share struggles and good practices. Their current campaigns are: Ratify C189, My Fair Home, and the Global Action Programme on Migrant Domestic Workers and their Families. Another global entity important for domestic workers is the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which is able to impact governmental policies thanks to its collective efforts with partners from more than 90 different countries.

Moreover, we can learn much from local initiatives that have contributed to improving the conditions and rights of domestic workers, in different parts of the world and using different approaches. Research is a fundamental step to better understand the situation of domestic workers and how to positively impact it. An example of successful evidence-based advocacy comes from Nepal, where research centers have carried out situational and policy analyses concerning emigrating workers, including domestic workers. The results became a powerful tool to pressure the government to adopt the Foreign Employment Act in 2008, with gender-sensitive provisions.

Organisations are increasingly using technology to reach as many domestic workers as possible. In particular in Uruguay, innovative methods have been used over the years, including radio and TV broadcasts as well as dedicated websites, to disseminate information and raise awareness. In Brazil, a mobile app was developed for domestic workers, providing them with accessible information on their rights, useful contacts of protection agencies, and the possibility to connect with each other through social networks. Lebanese project PROWD (Protecting the Rights of Domestic Workers) developed a successful on-line tool for groups and stakeholders to actively disseminate information and coordinate. [14]

Apart from research and awareness-raising, civil society organisations have done important work not only to obtain reform in laws and policies, but also to increase compliance and effective enforcement of relevant legislations, reaching results that have an impact on the lives of many. Moreover, they often have the knowledge to tackle specific contextual problems. The members of the Latin American and Caribbean Confederation of Household Workers CONLACTRAHO[15] have focused their activities on women from specific ethnic and social backgrounds which are traditionally and stereotypically associated to domestic work in the area. In Chad, Femme Juristes du Chad has brought forward the plight of domestic workers from rural areas.[16] In rural Samoa, the Samoa Victim Support Group is supporting nofotane women – married to a man from a different village, living with their in-laws, and exploited as domestic servants – to understand their rights and by advocating for the formal recognition and proper retribution of their work.

CONCLUSION: A LONG WAY AHEAD

This Newsletter does not aim at being an exhaustive resource on the issue of domestic work and domestic workers, but rather to give insight on the topic and raise some reflections on the human rights of domestic workers, in particular women.

Some positive steps forward have been made, but much still needs to be done for the rights and conditions of domestic workers worldwide, and women domestic workers especially. A law-and-enforcement approach is often advocated to solve the problems faced by this group, but here we argue for the necessity to adopt a human rights framework. Promoting, guaranteeing, and protecting human rights, in particular labour rights, in the everyday life of domestic workers is the first and fundamental step to lead to decreased informality and irregularity in the sector, and to recognise, value and promote the economic and social contributions of domestic workers in the society.

The struggle of women domestic workers is a struggle of the most vulnerable, of those who keep society going but stay invisible and without a voice, of those who engage in a day-to-day battle for their own rights and well-being. Mistreated domestic workers are not a distant reality, they are suffering close to us, in the private homes of every country. Scandals have involved even those who should fight inequality – diplomats, ambassadors, UN and EU staff.[17] As women’s and human rights advocates, we must put an end to this, to slavery, exploitation, and abuse. We must stand together with women domestic workers and support them in their call to finally and fully be recognised and valued by governments and societies.

This paper has been researched and drafted by Alice Vigani, intern at the President’s Secretariat of IAW, under the supervision of Joanna Manganara, President of IAW

[1] From https://www.antislavery.org/impact/stories/angel/

[2] ILO, Decent work for migrant workers: Moving the agenda forward – Executive Summary. Geneva, 2016

[3] ILO, Global estimates on migrant workers: Results and methodology. Special focus on migrant domestic workers. Geneva, 2015

[4] The Post-2015 Women’s Coalition (now Feminist Alliance for Rights), An issue brief: Unpaid care and post-2015.

Also see: UN Women, “What is the real value of unpaid work?” video, 2017 and UN Women News, The work that makes other work possible, 2016

[5] FRA. Severe labour exploitation: workers moving within or into the European Union – States’ obligations and victims’ rights. Vienna, 2015

[6] ILO, Formalizing domestic work. Geneva, 2016

ILO. Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204)

[7] HRW, The Domestic Workers Convention: Turning new global labor standards into change on the ground, 2012

[8] HRW, Protect domestic workers from violence: Many nations have failed to stem mental, physical, sexual abuse, 2008. At: https://www.hrw.org/news/2008/11/24/protect-domestic-workers-violence

HRW, “As if I am not human”: Abuses against domestic workers in Saudi Arabia, 2008. At: https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/07/07/if-i-am-not-human/abuses-against-asian-domestic-workers-saudi-arabia

HRW, Saudi Arabia: Protect migrant workers’ rights, 2013. At: https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/01/saudi-arabia-protect-migrant-workers-rights

[9] Migrant Rights Statistics, Domestic workers in the Gulf; High rates of suicide; Low wage workers. Available at: https://www.migrant-rights.org/statistic/domesticworkers/

[10] Quote extracted from: WIEGO, Yes, we did it! How the world’s domestic workers won their international rights and recognition. Cambridge (MA), 2013.

[11] Global map: Ratifications of C189 and law & policy across the world. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/genericdocument/wcms_313678.pdf

For an up-to-date overview of the C189 Ratifications by country, visit: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:11300:0::NO::P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:2551460

[12] 2014/51/EU: Council Decision of 28 January 2014 authorising Member States to ratify, in the interests of the European Union, the Convention concerning decent work for domestic workers, 2011, of the International Labour Organisation (Convention No 189)

[13] WIEGO, Domestic Workers around the World: Organising for Empowerment. Cape Town, 2010 .

ILO, Improving working conditions for domestic workers: Organizing, coordinated action and bargaining. Issue Brief No. 2: Labour Relations and Collective Bargaining. Geneva, 2015

ILO Gender Equality and Diversity Branch, Domestic work, wages, and gender equality: Lessons from developing countries. Geneva, 2015

UN Women Fund for Gender Equality, FGE Thematic Factsheet: ‘Leaving no one behind’ in action. New York, 2017

[14] ILO. Protecting the rights of migrant workers: Good practices and lessons learned from the Arab Region. Beirut, 2015

[15] In Spanish, Confederación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Trabajadoras del Hogar

[16] Read more in French on the IAW website

[17] See the sample news article on the UAE Ambassador in Ireland and documentary on EU officials in Belgium. For counter-measures, see: Global Forum on Migration & Development. Round Table 3.3 – Protecting Migrant Domestic Workers: Enhancing their Development Potential (Background Paper). 2002

The document may be downloaded here:

DOMESTIC WORKERS – President’s Newsletter May 2017