Written by Lydia Harper, UK, IAW Intern.

Written by Lydia Harper, UK, IAW Intern.

WHO defines FGM as including ‘procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons’, the practice is a violation of human rights and an attempt to control women and girls bodily and sexual autonomy. FGM can result in bleeding, problems urinating, sexual problems, psychological trauma, infections and many more complications including death (Who.int, 2018). In 2007 UNICEF along with UNFPA launched the Joint Programme to Eliminate Female Genital Mutilation; it is the largest global programme working towards this aim and focuses on 17 countries (Unfpa.org, n.d.). All of these nations covered under the programme are African, identified as having high FGM prevalence according to official data. However, FGM occurs globally and is a significant human rights and gender equality issue in some Asian and South American counties such as India, Indonesia, Iraq and Columbia (Asiapacific.unfpa.org, n.d.). The Joint Project reports that over 3.2 million girls have been positively affected by the project which works to build legal frameworks and guidance and promote enforcement; promote government ownership and engagement; and increase education and awareness through community led engagement (Unfpa.org, 2018). Within the analysis of Phase II of the programme, 2014- 2017 the importance of having a culturally sensitive human rights approach was recognised. The programme aims to support a change in the social norms surrounding and perpetuating FGM. By acting as a catalyst to accelerate change and reach a critical mass of individuals and communities turning away from the practice, alongside supporting legislation. Identified within stage II is the need to focus on empowering women and girls and supporting survivors of FGM, by challenging wider gender inequalities (Performance Analysis for Phase II UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation: Accelerating Change, 2018). By supporting community owned and women led, and focused projects change can be more sustainable and sensitive to culture and survivors. The Joint Programme’s focus on a human rights approach to change a social norm has the potential to be sustainable and effective in those areas targeted. However, as acknowledged in the analysis of stage II there needs to be a greater emphasis on centring women and girls as agents for change. Working with the support of legislation to promote dialogue, empowerment, community action and abandonment of FGM. The Joint Programme also fails to be global as is stated as it focuses on Africa and is lacking in its research and support in tackling FGM in Asia.

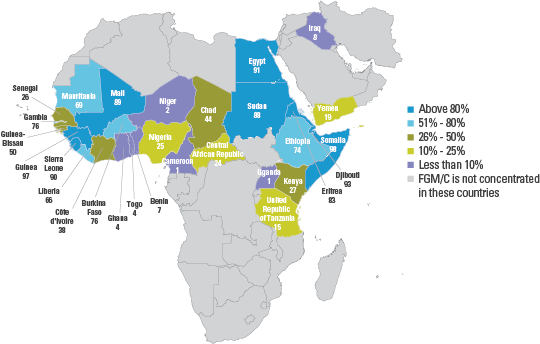

In 2016 UNICEF statistics declared at least 200 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to FGM (UNICEF, 2018), with the number of people subjected each year set to rise from 3.9 million to 4.6 million by 2030 (UNFPA, 2018). However, the prevalence of FGM has fallen by almost ¼ since 2014, the population growth in FGM prevalent countries is causing the number of women and girls at risk to continue to rise even as positive action is being taken and some attitudes are changing. Whilst prevalence of FGM is declining in most of Africa, where the most at-risk nations are, the real numbers of those at risk is rising on this continent and globally as population growth continues exponentially and more and more girl are born in to high risk countries (UNFPA, 2018). It must also be taken into consideration that this data is taken from official representative data from 30 countries, 27 of which are in Africa. FGM is practiced globally and in data published by the British Medical Journal in 2018 rates of FGM for those under 14 is rising in many Middle Eastern countries, often not included in global statistics. With gaps in data the full global situation of FGM cannot be understood (Kandala et al., 2018). Not only does this mean that resources and action and the recording and sharing of progress cannot take place it also means that the voices of the survivors are being ignored. FGM is a huge global issue, one that needs greater data collection from around the globe in order to form a baseline from which to track progress and trends and give greater understanding of the practice and ways to combat it.

In December 2012 the UN adopted a global ban on FGM (UN Women, 2012) and in 2016 the Pan African Parliament and the UNFPA signed an action plan to tackle FGM and child marriage in Africa (Figo.org, 2016). At the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 FGM was incorporated explicitly under goal 5 (gender equality) 5.3 ‘eliminate all harmful practices such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation’ with 193 countries signing the SDG’s (United Nations Sustainable Development, 2019). However, with 22 countries in Africa having national laws against the practice and 27 having signed up to regional and global treaties tackling the rates of FGM there is still a high occurrence of the practice in this region and globally (28 Too many, 2018). More Is needed than international declarations and bans. Half of all girls who have undergone or are at risk of FGM live in Egypt, Ethiopia and Nigeria all of which have laws prohibiting the practice, of course these countries are the three most populous in Africa, however this still serves as a demonstration that legislation is not enough to curb the practice of FGM (28 Too many, 2018). The power of international and regional guidelines and of national legislation is undeniable in that it serves not only to prosecute and limit the practice but also exists as a deceleration that the practice is not welcome and can indicate a change of attitudes. However, legislation has limitations and can push the practice underground.

For many girls around the globe the months of July, August and September are a high risk; during the school holidays girls undergo FGM, for some linked to child and forced marriage. Increasingly it can be seen that more girls are being taken to different countries during these months, to places with fewer laws or where legislation is weakly enforced. For example, those in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal are vulnerable particularly in along the border with Mali, where FGM laws are weekly enforced. Sometimes practitioners of FGM also travel during these summer months in order to carry out the procedure in different countries, this poses great challenges in prosecution when no crime has been committed nationally. It can also be difficult to identify families and young girls travelling for FGM in time to prevent the crime, there is therefore clearly a role for regional and international agreements to tackle FGM. Including collaboration across countries and border securities and an adaptation of laws to include those who travel or assist travel to carry out FGM (Kendi, 2018). Further to travelling to have FGM performed on girls and young women, data shows that the average age at which FGM is being performed is falling in some counties, this trend could be in response to tighter legislation and a greater need for the practice to occur in secret (Sustainabledevelopment.un.org, n.d.). Many girls and young women face increasing risks due to travelling for FGM and undergoing the procedure in secretive and underground settings. This also leads to a lack of representation in the data. In the 2018 UNFPA report ‘How to Transform a Social Norm’ the Joint Programme outlined the importance of engaging communities and changing attitudes towards FGM in order for a sustainable move away from the practice to occur (UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation, 2018). FGM will be carried out even if it means travelling unless it is voluntarily abandoned alongside legislation.

In other cases where legislation does exist it is often poorly enforced and sometimes inappropriate and outdated. In 2018 in Australia the countries first conviction against FGM was overturned on the grounds of the specific legal definition of FGM and in the USA a case was overturned which had resulted in FGM being performed on nine girls. This decision rested on the fact that the law against FGM was outdated and the decision was held at state level (Srinivasan, 2019). There are many obstacles that limit the number of cases successfully built and prosecuted against FGM including lack of awareness within police forces, conflicting attitudes from within the police and legal system, a lack of resources and access as well as stigma and secrecy both directed at those subjected to FGM and those who speak out against it and may alert the authorities. In response to some of these challenges Burkina Faso have developed mobile community courts delivering legal proceedings and raising awareness about the harms and laws around FGM within communities.

Cases such as those dropped in the USA and Australia demonstrate that the focus of these legal proceedings is not the protection of women and girls. FGM can be found globally and across history; propped up by religion, culture, health and tradition as a way to control and violate women’s bodies and sexualities. FGM as with other forms of gender-based violence such as child, early and forced marriage can continue to grow and thrive due to the gender inequalities and values within institutions such as the legal system. In working towards the elimination of FGM, action needs to be taken to tackle wider gender inequality; by supporting girls into education, community involvement and a realisation of their rights women are increasingly empowered and FGM rates fall. As recognised, the movement towards the elimination of FGM globally cannot be based purely on legislation and bans, grassroots activism and attitude shifts within many different cultures and communities must happen. Women, as the survivors and frontline activists looking to change the laws and practices must be centred as agents for change. The most effective way to tackle FGM is to empower women, from listening to accounts and collecting wider data to promoting access to education and most significantly by recognising local women as leaders and supporting them and their communities to change attitudes and behaviour at a local, national, regional and international level.

In India there is a lack of official data regarding the prevalence of FGM, this data gap is used to ignore and deny the issue of FGM occurring in India, largely amongst Bohras. Increasingly data is being collected with one study finding that of 94 participants 75% of their daughters had undergone FGM (Anantnarayan, 2018). Without representative and extensive data to establish a base line and with which to measure the changing rates of practices and monitor programmes it is not possible to fully understand the nature and extent of FGM in India. This lack of awareness, and in hand lack of action reinforces the culture of secrecy and allows FGM practices to continue unchallenged.

Working against this, Speak Out on FGM is a survivor led movement growing from a WhatsApp group started by Masooma Ranalvi in 2015 to share experiences and support. In the years following Speak Out on FGM has led campaigns, petitions and lobbying activities working towards having FGM fully acknowledged and legislated against in India and Bohra communities worldwide. In 2016, to align with the International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM Speak Out on FGM in partnership with Sahiyo lauched the ‘Each One, Reach One’ campaign which was repeated during Ramadan 2017 (Wespeakout.org, 2019). This campaign called for women to pledge to start one conversation with a Bohra friend or family member about FGM, by bringing the practice out of the shadows and beginning open discussions about its place in society these women risk shame, stigma and social exclusion. But with the beginnings of community conversations survivors’ voices are being amplified and heard and new opportunities are opening up. As can be seen when Speak Out on FGM ran it’s ‘Not My Daughter’ which saw 126 Bohra parents publicly pledge not to have their daughters undergo FGM (Wespeakout.org, 2019). This survivor led organisation empowers those women who share their stories and creates a louder voice for survivors of FGM over India and in Bohra communities globally. These women are uniquely placed to understand FGM and its effects and to understand the cultural and community forces that are key both in perpetuating and dismantling the pervasiveness of the practice. Following a case against a Bohra mother and midwife in Australia accused of performing FGM (Partridge, 2014) more attention was bought to the issue of FGM in the community and in 2018 a petition was brought before the Indian Supreme Court to create laws against FGM in India. The petition faced backlash by those who believe that to ban FGM is to act against religious freedom although this practice predates Islam and can be seen across many religions and cultures, the petition has been referred to a constitutional bench (Rajagopal, 2018). Sahiyo, the organisation jointly behind the ‘Each One, Reach One’ campaign similarly began as a conversation between five women who were speaking out against FGM within their communities. Through research, advocacy and awareness campaigns the organisation engages in community dialogue and empowers young women and girls to end FGM among Asian communities. Sahiyo have launched a petition ‘for the UN and other international bodies to invest more research and support in eradicating FGM in Asia.’ (SAHIYO, n.d.). With a lack of official data and limited international attention on FGM in Asia, survivor led organisations are breaking the silence around FGM and engaging national and international level institutions.

Jamila Mwanjisi the head of advocacy, campaigns and media for Save the Children Somalia/Somaliland recognises the importance of women as mother’s attitudes in eradicating FGM. ‘Women often act as perpetuators of this violence, encouraging and organising for their daughters and granddaughters to undergo the procedures in many places the procedure itself is performed by women.’ Therefore, women in the roles of mother and grandmother have power to lead the way in ending the practice of FGM, by starting conversations and taking decisive actions to change attitudes. Following are some case studies demonstrating the power of women turning away from FGM, starting conversations and empowering women.

In Nigeria the Frown Challenge calls on women to share their experiences of FGM on Facebook, by sharing a photo of themselves frowning accompanied by their experiences and thoughts each Frown Challenge acts as a public statement against FGM. The Frown Challenge reached half a million Nigerians within six months and engaged thirty celebrities. The social media campaign engages directly with young Nigerians and educates in a quick and accessible way about the nature and harm of FGM. With the aim of breaking stigma and starting a conversation this campaign involves Nigerians from many backgrounds and communities and is an easy way for many people to publicly declare against FGM paving the way for others to follow, it serves to amplify the voices of survivors and women speaking up against the practice (Olagoke-Adaramoye, n.d.).

Established in 2010 Think Young Women Gambia is a community-based, women led organisation that works on the principle that women and girls are vital and active parts of their communities. Following the mission of ‘Finding our voices in the power of change’ Think Young Women seeks to end gender-based violence by empowering women and girls through mentoring, public speaking, games, relationship building etc. To tackle FGM Think Young Women have led multi day community engagement campaigns, starting conversations about FGM in Sandu and Jimara districts. With discussions led by experts on the socio-cultural complexities, health consequences, religious perspectives, and legal provisions around FGM to promote greater discussion and community sensitive understanding. In listening to community members, raising awareness and empowering young women and girls Think Young Women is aiming to inspire an attitude change and encourage the voluntary abandonment of FGM in The Gambia (Thinkyoungwomen.org, n.d.).

Women are also leading the way in Columbia working to change perceptions and eradicate the practicing of FGM within some Emberá communities. Where FGM is practiced it is done so hidden and underground and there are no reliable studies to indicate how many women and girls may be at risk of FGM in Columbia. With the support of the UNFPA the Columbian Family Institute, along with Risaralda Indigenous Regional Council launched the Emberá Wera (meaning Emberá Women) project. This was possible in part due to the work of Ms. Zapata, who broke norms by taking a key position on a Regional Indigenous Council without the traditionally required support of her husband. She assumed the role of Regional Advisor for Women’s Issues. In carrying out the Emberá Wera initiative Ms. Zapata and a group of women travel to Emberá communities and work with women, traditional birth attendants and indigenous authorities to start conversations around and promote education on the harm of FGM. The project aims to empower women and promote autonomy and, as said by Ms. Zapalta it gave her and many other women, the confidence to speak out, demand change and become leaders (Unfpa.org, n.d.).

These three movements show how women led conversations and networks of women and community leaders can lead change from within the community by sharing experiences, breaking the silence and offering alternatives. Furthermore, as has been seen that population growth is a huge issue faced in the eradication of FGM, therefore the key is to work towards the generational rejection of the practice. By placing women and community leaders at the head of the movement then the next generation of girls are being given a chance to escape FGM and have greater realisation of their personal agency. As traditional performers of FGM are turning away from the practise and mothers and grandmothers are discussing their trauma and vowing to spare their children from it a change in attitude and behaviour can be seen growing from the community level.

FGM is often part of traditional coming of age and forms a rite of passage into women hood, this forms part of the social ostracising individuals may face if speaking out against the practice and amounts to pressure on women and parents to have FGM performed on their relatives. In Tarime, Tanzania UNFPA support the Terminate Female Genital Mutilation programme part of which is an alternative rite of passage (Unfpa.org, n.d.). The programme runs the Masanga centre which serves as a refuge for those fleeing FGM, child and forced marriage, during a one month programme girls are educated on human rights, sexual and reproductive health rights, the culture of their Kuryu community and given extra school tuition. The programme ends with a graduation ceremony and acts as an alternative rite of passage for girls in the community, these young women are empowered to start further community conversations and protect their daughters and family members from FGM, over 2000 girls have received the alternative rites of passage here.

Many traditional practitioners of FGM are women; the performing of the ritual is one passed down generationally and provides a source of income for these women. These women turning away from their practices is key in working to end FGM, it makes a strong statement to the community as well as reducing opportunity for girls to undergo the procedure. Whilst some women turn away from the practice out of fear of prosecution under legislation against FGM for many there is an investment in the continuation of the practice. The Masanga centre in Tanzania works with the ngariba (traditional FGM practitioners) to educate about the harm of FGM and human rights. The centre provided entrepreneurial and skills training to support the ngariba in earning and income and maintaining autonomy whilst protecting girls and ending the practice of FGM. Since 2014 11 ngariba’s have stopped performing FGM after dialogue and work with the Masanga centre and the district government (Unfpa.org, n.d.).

The work of the Masanga centre in Tanzania demonstrates the significance of working with and centring women and girls as agents of change, for sustainable change to occur it must be led by those with an understanding of the deep- rooted meanings attached to FGM.

There is a need for campaigns against FGM to be holistic, with long term community investment and organisational support alongside tackling larger structural gender inequalities (Johansen et al, 2013). Data suggests that large international organisations and governments providing aid to the promotion of gender equality provide a very limited amount of these donations to groups located in the countries receiving aid (Oecd.org, 2014). Many campaigns against FGM have a ‘one size fits all’ approach. For example, transplanting the same teaching materials into different communities (Brown, Beecham and Barrett, 2013). They are therefore less effective as they do not work with community values and beliefs. This kind of campaigning also fails to address the underlying power structures and gender relations. By focusing on long term, locally adapted investment and emphasising gender parity throughout the community sustainable change can be better achieved.

As we have seen, national, regional and international legislation and focus on the eradication of FGM yields patchy results. Some states deny the existence of FGM in their nation, as with India, or acknowledge the practice occurs but have limited data to focus resources and map progress. In some places the increased legislation is not in tandem with social norms and trends and therefore is ineffectively enforced and can serve to push FGM practices underground. Further, legislation alone can be difficult to prosecute with and the defeats in the USA and Australia serve to reinforce and normalise this practice and further silence the voices of the survivors. Recognising that this practice operates as a form of control and violation of the female body and sexuality and is, whilst propped up by religion, culture and tradition a practise of gender inequality it becomes clear that the movement against FGM must be a movement by and for women. Regionally, nationally and globally women and community led organisations have the power to recognise, call out, campaign against, educate and guide legislation against FGM.