The last year has brought troubling events for feminists who are striving to see more women win top political leadership positions. Two female presidents, Dilma Rousseff of Brazil and Park Guen-hye of South Korea, had to leave office amid corruption scandals. In the United States, a female candidate did not become president: Hillary Clinton.

The last year has brought troubling events for feminists who are striving to see more women win top political leadership positions. Two female presidents, Dilma Rousseff of Brazil and Park Guen-hye of South Korea, had to leave office amid corruption scandals. In the United States, a female candidate did not become president: Hillary Clinton.

Female politicians are often met with skepticism because of their gender, and Clinton was exposed to clearly misogynist attitudes. Whether the two female presidents of Brazil and South Korea were judged more harshly than men is difficult to say. No one wants corrupt politicians, but both of those countries are flawed democracies. It would take deep analysis to determine whether women were more exposed, caught up more easily or criticized more severely for gender-related reasons to explain their downfalls.

What’s clear is that the number of female top leaders globally was small last year, dropping from a record high of 24 in 2015 to 20 in 2016.

My country, Norway, is described internationally as a “gender equality winner,” but we have never exceeded 40 percent of women in parliament and local councils, so the women’s movement here still has work to do. Norway is holding general elections on Sept. 11, and 40 percent of the candidates are women, including the incumbent, Erna Solberg, of the Conservative Party.

Solberg is the second female prime minister of Norway, and we have at times reached gender parity among ministers in the cabinet, yet counting the political advisers and state secretaries reflects a solid male-dominated government. Researchers note that Norway’s gender-equality policy has failed, especially as men control the economy and the media as well.

Throughout the world, bringing women into political power has been a long, slow process ever since the United Nations proclaimed the equal rights of men and women in 1945. Since then, 100 women in total have gone to the top with widely varying impact in 66 countries worldwide. Only North Africa and the Middle East have never had a female national leader, and there has been only one in the Pacific region, in 2016.

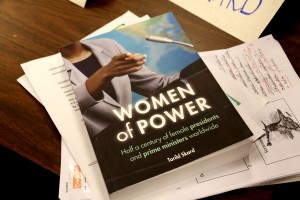

Each female leader has her own special story. But studying the 73 women who rose to the top in 53 countries from 1960 to 2010 for my book, “Women of Power,” certain trends can be discerned.

Rich democracies in the forefront

Women rose to power more often in industrial than in developing countries. People’s health, education and income made a difference. Most of the female national leaders had exceptionally high education and professional careers. The improvement of living standards, not least for girls and women, represents a positive factor for women’s participation in politics. Most female national leaders rose to power in democratic systems. Particularly after the end of the Cold War, the number of democracies increased globally, as did the number of female leaders.

In 2016, about half of the world’s nations were democracies, while the rest had authoritarian or hybrid regimes. The great majority of democracies, however, were “flawed,” according to the Economist’s Democracy Index. Even the “standard-bearer” of democracy, the US, was downgraded from “full” to “flawed.”

This means that there were faults in the electoral process, civil liberties, political culture, political participation and functioning of government. These factors led to the election of a US president, Donald Trump, who among other matters, disrespects democratic values and women’s rights.

In democracies, political parties are the routes to power, and most of the female national leaders in the world obtained a position of power through such parties. There is limited research on these fundamental political institutions, but it is noted globally that they are extremely male dominated.

Although 40 to 50 percent of party members are women, women hold only about 10 percent of the leadership positions. In fact, we see an iron law of power: the more power, the more men. In 2016, there were 23 percent women in the world’s parliaments, 18 percent in the cabinets and 7 percent among the national leaders. Besides the political leadership, the economy and the media were also dominated by men. Misogynistic sentiments permeated public and private spheres, making political participation difficult for women.

In politics, the electoral system is crucial. Considerably more women became national leaders in countries with proportional representation than those with majority vote, as the latter favors men. In parliamentary elections, legislative reform and quotas have helped to increase the representation of women, but more ambitious measures are needed.

Indications show that the general involvement in political parties is declining right now, not least in industrial countries, weakening their position and opening space for monetary power, financial interests and lobby groups. Election turnout is also declining as democratic disillusion is spreading. If a certain democracy is necessary for women’s participation in power structures, it does not mean that it is enough. There must be a demand for women in decision-making.

Norway would never attained so many women in parliament and the cabinet and two female prime ministers without the efforts of a persistent women’s movement in place over many years. The UN, in collaboration with the women’s movement have been driving forces for gender equality internationally and nationally. The great majority of female national leaders benefited from female voters and female activists requiring more women in leading positions. And most of the female leaders did something to support women. They made a difference, though it was often limited.

Read the whole article, which was first published by PassBlue, which is a nonprofit journalism site wholly dependent on donations.