Militarism, masculinity, violence

Militarism, masculinity, violence

Militarism is normally understood as the preponderance of military values and interests in politics and society based on the concept that wars are inevitable. It is a way of thinking about a proper hierarchical division of the world, based on order and obedience. “It is built through the construction of the “enemy”, the indoctrination of children, and the creation of myths about the nation and the other” (Center for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL) at Rutgers University, meeting 2011 on “violence against women and militarism.) “As a result, militarism is linked to nationalism. It is about control and the power relations that buttress militarism and exposes the ways in which male violence is constructed as a legitimate form of control”.

In the end, it is about control and power of definition.

In an important joint NGO statement to the CEDAW Committee submitted on the occasion of the General Discussion on Women in Conflict and Post-conflict Situations, July 18, 2013, endorsed by IAW, it is stated that “peace at home and peace in society are interlinked. A culture of militarism intimidates women from asserting their collective and individual rights, including the right to vote and participation in political decision-making. Families with ex-combatants often experience increased levels of violence”. According to CWGL “ Domestic violence becomes even more dangerous when guns are present in the home” According to the International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA), women are three times more likely to die violently if there is a gun in the house.

“Conflicts everywhere”, as it was stated at the Nobel Women’s Initiative conference, May 2013, Belfast, “target young men – and especially ‘alienated’ young men”. For Madeleine Rees (WILPF) the key problem is also – in part – one of masculinities. “War necessitates and reproduces a type of masculinity that is prepared to go and fight – and even kill – for something. Dominant models of masculinity, in turn, draw on a militarised idea of the nation.”

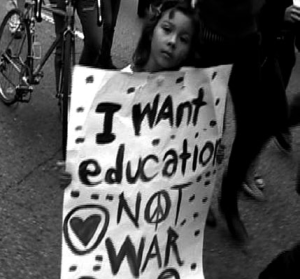

According to the joint NGO statement, prevention is a high priority, including first and foremost the “regulation of possession, sale, trade and criminal use of legal and illicit small arms and light weapons”…”Best practices to contain widespread harm to girls and women during conflict require further study and financial support. These include engendering early warning systems…for instance, as has been proposed by the African Union, through women’s networks serving as sources of information concerning conflicts.” Investment in education (instead of in arms manufacturing) is regarded as one of the most strategic measure to ensure personal security.

Both prevention and education are in no way new strategic goals in IAW policy making. Their application in the context of IAW’s Peace Commission policy as reflected in our Action Programme 2008-2010, could trigger innovative interlinkages and unexpected results. Please become part of safety-voices-choices by contacting: iaw.peace@womenalliance.org.

Military versus social spending

“There is no business like the arms business”. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), total world military expenditure in 2012 was USD 1.75 trillion. This is equivalent to 2.5 per cent of the global gross domestic product (GDP). Do we have any idea what 2.5 of the global GDP would represent for social spending? Fortunately, the Campagne tegen Wapenhandel (www.stopwapenhandel.org) gives us some ideas when asking how many jobs could be created with a USD one billion investment. The answer: 8,555 in the military, 10,779 in personal consumption, 12,804 in construction, infrastructure, 12,883 in health care, 17,687 in education, 19,795 in public transportation.

Another important source of information, published by the World Council of Churches in 2005, is a compilation of data and facts related to military spending, education and health. In its Foreword mention is made of “a silent deadly disaster taking place every day in the starvation of 24,000 people, many of whom could be saved if the world had not gotten its budget priorities so utterly wrong”. An international and interfaith “Global Priorities Campaign” (www.globalpriorities.org) states that “one half percent of the world’s military spending would save 6 million children from death each year”. Finally, the World Game (www.worldgame.org) has calculated that one third of the world’s military spending would satisfy budgetary needs for addressing all global problems, from deforestation to HIV & AIDS, from clean water to illiteracy.

For a feminist organisation such as the Alliance, it may be interesting to note that it was a woman, Ruth Sivard, who first published a comparison of military and social spending by world governments. Ms Sivard had been a high-ranking economist for the US State Department and the Arms Control and Disarmament Administration. She was able to find reliable sources for the detailed statistical information she published.

Some IAW peace herstory:

Up to the Geneva Congress in 1920, the Alliance was guided in its activities by its Charter drafted in Washington in 1902 and the goal adopted at the Congress in Berlin in 1904. Accordingly, it concentrated on the right of women to vote, the political empowerment of women, persuaded that this would bring about the power of decision so much needed for women in every political field. In 1914, however, 10 years after its inception, the Alliance (at the time the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, IWSA) saw itself “faced by the disruption, the animosity, the misunderstanding caused by war”. The Manifesto drawn up by the IWSA and delivered on July 31, 1914 to the Foreign Office and Foreign Embassies in London speaks for itself and remains one of the pillars of IAW’s policy for peace and international understanding. In this forthcoming year – the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of WWI, today’s IAW still upholds the principles of “conciliation and arbitration for arranging international differences.”

A first sign of changing positions was the new title of the Alliance adopted by the Paris Congress, 1926: International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship. This indicated its wider, more comprehensive aims, including peace and support for the League of Nations. The resolution adopted at Paris that a permanent peace committee should be formed led to the establishment of the “Committee for Peace and the League of Nations”. In 1927 this committee proposed holding a study conference in Amsterdam the same year on aspects of the maintenance of peace and the study of the economic and political causes of unrest. It is interesting to note that IWSA organised a further peace conference in May 1931 in Belgrade. This conference passed three resolutions: on disarmament, on international economic co-operation, and on participation of women at the forthcoming multilateral disarmament conference.

At its Jubilee Congress in Berlin in 1929, the resolution on “Peace and the League of Nations” declared “that it is the duty of the women of all nations to work for friendly international relations, to demand the substitution of judicial methods for those of force, and to promote the concept of human solidarity as superior to racial and national solidarity”.

Starting with the first International IAW Congress after WWII in Interlaken, August 1946, peace continually remained on IAW agenda. (Here another important change of title took place: International Alliance of Women – Equal Rights-Equal Responsibilities). Congress adopted an important peace resolution “protesting against the use of atomic energy as a weapon of war”, urging “that the sources, scientific development, manufacture and use of atomic energy for all purposes be under the control of the United Nations” and “calling upon its members to unite in a common effort so that full support may be given to the new organisation (UN) and the principles upon which it is based”, and thereby ensuring “through national and international co-operation that the professed ideals of a community of nations, the unity of mankind and the universal brotherhood of man, may be translated into a living reality”. Congress participants also signed a petition addressed to the multilateral Paris Peace Conference of the same year. They express their hope that the treaties coming out of this conference might build a world order based upon justice and the right of people to live in freedom and harmony, protected against all forms of aggression.

Since then, IAW never ceased its efforts to “conciliate and arbitrate”, at national and regional levels through its member organizations and individual members, and through its advocacy in cooperation with the United Nations and other multilateral organizations. It was therefore with great enthusiasm that IAW welcomed Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) and its following resolutions, forming the backbone of today’s efforts towards reconciliation, rehabilitation and reconstruction – including the full participation of women – after conflicts and humanitarian crises.