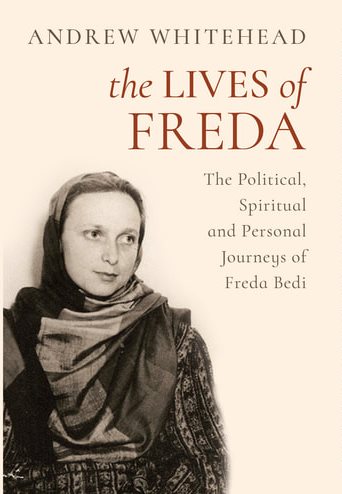

The Lives of Freda

The Lives of Freda

The political, spiritual and personal journeys of Freda Bedi

Andrew Whitehead

Speaking Tiger INR 499/

A Hollywood star and a Buddhist nun – a combination that seems rather strange unless you consider Richard Gere. In this case the movie star is Kabir Bedi, famed for cameos in the James Bond Octopussy and the Buddhist nun his mother Freda. Neither he nor his sister approved of his mother’s devotion to the Buddhist cause and felt that she had abandoned her children but nonetheless his mother was adamant.

The Lives of Freda outlines the life of an unusual woman, a English woman who married a Sikh fellow student whom she met in Oxford at a time when interracial marriages were frowned on in the British Empire. Freda’s marriage was ultimately accepted by her mother but she struggled to overcome her foreign roots in the Indian subcontinent. She and Baba Pyare Lal Bedi formed an intellectual partnership publishing magazines and analytical essays while being staunch communists together. They lived in Berlin while Hitler was coming to power and then they were thrown into the turmoil of Partition, more so because Bedi’s family home was in Lahore. As a journalist she wrote a column on women’s issues though some people said her viewpoint was more English than Indian.

They rubbed shoulders with political figures and were both thrown in jail by the British for joining the cause of Indian independence – though in Freda’s case she was one of Gandhi’s first satyagrahis and one of the first non-Indian women to be jailed for her role. What emerges is Freda’s dedication and her ability to carry out her publishing work, her politics and raise her children – though there were gaps between her first born and the other two, she lost a child to dysentery in the middle. Freda organised gardening groups in jail and when she was released and she and her husband moved to Kashmir. There she involved herself with woman’s organisations trying to spread the cause of sanitation, pre birth and post birth care and deal with rape victims. She also, along with her eldest son Ranga, ended up cleaning bloodstains in a church in Baramulla where the congregation had been massacred. Ranga at 12 was carrying secret messages in his schoolbooks to the Kashmiri undercover agents while his mother was totally unaware of the fact.

From this is was a small step to caring for the Tibetans who flooded to India in the wake of the Dalai Lama. They were housed in refugee camps and Freda pleaded with Nehru to be allowed to work for their cause. Andrew Whitehead is an appropriate choice for biographer since he spent a great deal of time in Delhi working as a journalist and bringing up his family. He goes into great detail where her work for the Tibetan refugees is concerned, notably her association with the various lamas and the school she set up for young incarnate lamas – many Buddhist nuns in fact saw her as an incarnation of White Tara.

The book draws on papers belonging to Kabir Bedi and highlights Freda’s independence and sense of self. Despite being British she saw herself as Indian and struggled for that identity. She was in fact upset when she was given an award for the work she had done as a foreigner for India. Ultimately her personal life is slightly glossed over – issues like her relationship with her husband who was a womaniser but nonetheless loved her dearly, her separation from the Communist cause or why she chose to become a nun without telling her children will remain somewhat of a speculation. Also the fact that despite clinging to her Indian identity, everyone who met her in her Buddhist incarnation commented on how much the Memsahib she was. What remains unquestioned is her sincerity and dedication to the cause of women, freedom and spiritual matters.